Friday, January 28, 2011

A drastic decision...

Deeply and profoundly inspired by my recent reading of Sam Harris's fabulous book, The End of Faith - astonishingly competent and important - I have arrived at the epiphany to overtly make the clean bold break that has been natural to me for decades now and announce point-blank that I am not a Christian. I have held on to being a "moderate" and espousing the tradition due to my great respect for the genuine spiritual master Jesus Christ. But Harris enlightened me to the error of my ways and I now see clearly the immorality of condescending to endorse the warped tradition ostensibly associated with Jesus' name.

Of course only one "Christian" in a million has a clue to the original teaching. Most have never even heard of - much less read - the most important of the gospels, namely, the Gospel of Thomas. But anyway, faith as the term is socially understood (unrelated to anything valid as a tool for salvation) is inconceivably dangerous. It is the main thing wrong with the world, second only to sleep (our ordinary state we live out our lives in, including our fantasy of faith). What is needed is empirical and practical spiritual practice.

I will continue to claim to be a Buddhist since that is so amenable to that. But for an example of practical empirical spirituality, in my opinion Jeanne de Salzmann's book The Reality of Being is light-years beyond the average person in its spiritual wisdom and is the most precious and sacred book existing for those who would take it on in a serious way. I take my spiritual life very seriously at least in principle, regardless of how feeble it plays out in my actual effort. As for the most important book in the world in terms of what most people in the world desperately need to read, I pick Sam Harris's book.

Saturday, January 1, 2011

The posts most worth reading...

Briefly, you notice I am not a very active blogger, and most of my postings have derived from my schooling for my masters degree in liberal studies where blog posts were required. Here it is 2011 and there is nothing posted for 2010! However, you should read the June, 2008 blogs on mystical topics if nothing else; especially if you are interested in knowing something about my way of thinking. Top on the list are the ones on proper definitions of mystic and mysticism, the epistemology of revealed truth, the fallacy with the long awkward name, the quote on mystical authority, and the "most important" essay on consciousness.

Monday, August 31, 2009

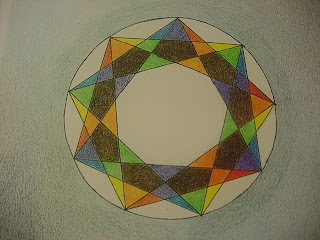

Third order enneagram

Hello! The image seen here is a mandala pattern I created strictly from following the application of certain principles or "laws" as given within a certain esoteric school. The point to be noted is that this art is explicitly a repository for certain knowledge that can be read from it by those who know the laws of its construction. In a way it is almost dishonest for me to claim it as my creation, even though there is no one else available for such a claim. The laws of its creation dictated the composition absolutely. All I did was draw it and color it. This diagram uncolored resembled the crown (top part) of a round cut faceted stone. So after three years of research and development I along with some lapidarists and their GemCad computer program developed a facet design that enabled the creation of faceted stones with this design. The first one ever created was publically presented for the first time on the first Monday of the new millennium, so I nicknamed it the Millennium Stone. It was a 187 carat rock crystal quartz. The second was 130 carats in rock crystal quartz and just recently an amethyst has been commissioned and funded. Incidentally, to be clear, the people promoting the so-called enneagram as a tool for the psychology of types don't even know what the enneagram is. They stole the idea as a marketing tool. The original primary source on the enneagram does not even mention the psychology of types in connection with the enneagram, which is presented in its first order version. Steve

Friday, August 28, 2009

Art as experience

Art is indeed a universal language, even if not simplistically so. Or perhaps more accurately, it is a whole set of varied universal and quasi-universal languages. Notice that “language” and “communication” are not synonymous. Language exists for the sake of communication but is no guarantee of success for it. Art is always a manifestation of experience which in turn is grounded in consciousness. The universality of art is therefore tied to the extent and manner of human experiencing, which in turn varies not only according to a horizontal expanse of cultural and historic diversity but also to a vertical hierarchy of being not commonly perceived for its full extent and relevance. These patterns – both horizontal and vertical – are at the heart of the dynamics of art both in terms of its manifest holism and its manifest diversity and creative autonomies. To the extent that holism is manifest, the language has communicated universally. To the extent that diversity and creative autonomy dominates the communication of artistic expression, such communication may be segregated. Yet the interface of experiencing between the art and its audience constitutes a universal principle (or perhaps a set of them). What has changed is the composition of the audience.

Our own personal lens and cultural viewpoints affect our capacity to truly appreciate another culture’s art, but it does so variably and is not the only variable setting the parameters of that capacity. To the extent that the differences in art among cultures is simply a consequence of cultural differences, we can learn to transcend our restricted capacities by learning more about the culture and its art and trying to put ourselves in their place not just conceptually but experientially. Of course art is a medium that is conducive to that. To some extent that is a main point about art as regards culture, given its facility for transcending cultural barriers.

But there are also hierarchical differences. For example, in his book “A New Model of the Universe” Russian mystic philosopher P.D. Ouspensky related personal accounts of his experiences visiting great works of ancient spiritual art including the Sphinx, Notre Dame Cathedral, a Buddha with sapphire eyes and others. What was communicated to Ouspensky in these experiences went far beyond the typical tourist with camera in hand. But at the same time, his experiences were also not merely subjectively personal. As a mystic myself I can vouch for how this can be. The art works were conveying real information – not rationally-based information perhaps, but often emotionally based – but information nevertheless. The information was presented by Ouspensky as universal, intrinsic to the works of art, and perceivable in the same way to anyone with a suitable state of awareness (less “asleep”). Accounts by other people support these conclusions. The esoteric master G.I. Gurdjieff explains that some of these works - he called them “objective art” – were created for the express purpose of being a repository of certain knowledge perceptible in certain states or with certain preparation.

Even in less transcendental examples, we see hierarchy at play. One of our class members spoke of pop music as an expression of specifically American art, and noted the rarity and neglect of the classics. My question is, are you going by consensus on the assumption that aesthetic criteria are democratic? I’m not saying that’s wrong, but I will say it is incomplete. Who could possibly deny that Aaron Copeland, George Gershwin and Leonard Bernstein represent American music and art in a quintessential and fundamental way? Applying the idea of hierarchy, these composers could churn out sophomoric grades of pop music in their sleep by the truckload. But most of the American pop musicians – Michael Jackson included – would never be able to produce a large scale musical masterpiece of the caliber of Copeland’s “Rodeo” or Bernstein’s “West Side Story” even if you held a gun to their head. And people claiming that the only criterion of aesthetic judgment between them is “taste” are categorically wrong. A pig cannot understand fashion but a fashion designer can grasp the nature of a pig. Another pig saying the two are on the same level merely discloses its level on the hierarchy – that it is confined to the level of the pig. The claim as aesthetic philosophy carries no credibility.

This leads to the question of a translation process. What translation of fashion is possible to a pig? None. So translation is only possible to people who have what Plotinus called “adequatio” – they must be of comparable hierarchy in their aesthetic sensibilities. So a person whose musical sensibilities are on the level of rap or ACDC who says their music is as good as Beethoven’s and that one person’s opinion on it is as good as anyone else’s is totally full of crap. They are like a pig who says their mud is on a par with a Paris original gown.

The issue of translation is fundamentally epistemological. Those of you who have had me in prior MALS classes know you can scarcely have a discussion with me about anything without knowing the word “epistemology”, which is philosophy of knowing. For example, “this apple in my hand is red” is a different kind of knowing and truth claim from “according to Wikipedia the capital of Bolivia is La Paz.” For both truth claims to be the same kind you have to go to La Paz. Plotinus’s “adequatio” spoken of above is about epistemological hierarchy. But notice how epistemology leads directly into our final question: What are the most basic, globally shared, human experiences? While many examples come to mind, I wish to concentrate on what I believe to be the most basic and fundamental and shared of them all: consciousness (which, incidentally, is itself quite hierarchical). This is no mere tautology, and far from inconsequential to our inquiry. Our question is about human experiences. What kind of experiences do you have in a coma? And here I might as well interject as a scientist that the Newtonian worldview of a universe of dead matter and energy in interaction with a human perceiver inserted separately and anomalously like a ghost in a machine is a century obsolete. We do not live in such a universe. The data of science adamantly does not support such a view and educators who present it are outmoded and irresponsible. What does that have to do with this discussion? Actually a great deal. Experience is as fundamental to reality as matter and energy. And the Cartesian subject/object dualism is not valid. Therefore there exists a kind of intimacy between perceiver and perceived and object of perception. There is nothing more fundamental in art than the actual experience a person has with the art. The art actually exists as art in the experience of it in the moment, in which the art and the experience are united in the experience. That experience has as much ontological validity – as much “reality” – as the art itself and the experiencer itself. The central hub behind all of the qualities that make art art is just this experience in the moment. It is the “sound of one hand clapping” in Zen. Aesthetics is nutrition of experience. Quoting a dear mentor, I wish you good digestion.

Sunday, June 22, 2008

Unsung genius: the overlooked Jungian analyst

Many so-called “depth” psychologists have very little acquaintance with the Jungian analyst Dr. Maurice Nicoll. The historical context is helpful for understanding this anomaly. At the time that Alfred Adler was studying under Jung (he had already asserted his autonomy from Freud), Maurice Nicoll was there with him. Several biographers have noted that Jung had attached a great deal of promise to both Nicoll and Adler, but that in 1921, Nicoll parted company and never looked back. Adler, of course, became an important psychoanalyst and theorist in his own right, one of the first to emphasize social factors in the development of personality. Nicoll was essentially discarded by the mainstream, and in fact Freud is quoted as making a snide remark about him. But Nicoll was actually transcending and not betraying his Jungian background, as his later writings make obvious. Nicoll was a seeker, looking for the clues to transpersonal development. Nicoll had many friends among the psychologists, psychiatrists, authors and physicians associated with the influential quarterly, The New Age with its brilliant editor A.R. Orage. Banding with them, they created a “psychosynthesis” group long before Roberto Assagioli made the term commonplace. Among the group, Rowland Kenny wrote in the fall of 1921 about psychoanalysis that, “it would never help one to re-create one’s own inner being… What we wanted, we decided, was a psychosynthesist.” (Webb). The psychosynthesis group included Havelock Ellis, David Eder, James Young, Rowland Kenny and Maurice Nicoll along with a few other occasional contributors. But as biographer Beryl Pogson details dramatically, it was the introduction to Russian philosopher P.D. Ouspensky in August, 1921 that inspired Nicoll to strike out boldly in a new direction. Nicoll felt that he had found just what he was looking for. And he found it among people who were not established in western academia. Never mind that the scope and depth of vision of what he found far surpassed the western academia he was leaving behind. If you don’t play the game according to the rules, you are trash who existence does not dignify recognition. Therefore, the very Jungian analyst who did the most to show the extent to which Jungian concepts can be successfully employed in the pursuit of transpersonal development and its psychology is the one who name has been deliberately erased from history and science.

It is not uncommon to ascribe a mystical dimension to the work of Carl Jung, who himself endorsed a mystical element as important to his psychology. Jung’s own epistemology of mysticism, however, to the extent that it even exists suffers from inappropriate formulation and reductionism. He nevertheless remains in contrast to some of his followers who have retained his psychoanalytic constructs but thoroughly eradicated all transpersonal elements of his teaching. Don’t assume I’m being naïve here – I am aware that some retain the language. But they have violently annihilated what little transcendental meaning was there in the first place. A good example is James Hillman. Having nothing constructive to offer himself apart from rejecting Cartesian dualism and announcing the lack of unity in ego, Hillman does Jungian constructs a great disservice by restricting their domain to the lower fulcra of developmental psychology (as outlined by Ken Wilber). The result is that their remarkable efficacy for the higher fulcra remains undiscovered. Were it not for the spectacular work of Nicoll in this regard, the Jungian genius in its application to transpersonal psychology would remain largely unknown and unexplored. Jung himself never came close to seeing it as Nicoll did.

Nicoll has important contributions to make in the fields of psychology, Christian theology and in metaphysics. In psychology, his magnum opus is his six-volume set called Psychological Commentaries on the Teaching of Gurdjieff and Ouspensky. He could have just as well added Jung in the title, as the application of Jungian constructs is almost universal throughout. These two diverse strands of thought, Jungian psychology and fourth way esotericism – along with a third of Christian scriptures - are so seamlessly and harmoniously integrated in these commentaries that it seems they were intended for amalgamation all along. Nicoll applies Jungian constructs to Christian scriptures and to esoteric teachings with an ease and a fit that suggests inevitability. Each of the three strands enhances the other two and reveals additional depth and genius to the originals. In Christian theology, Nicoll has two small jewels. The Mark is a book examining to a large extent Old Testament scriptures. This work only looks second fiddle when compared to the little masterpiece The New Man, which exclusively examines the canonical gospels. The New Man is easily one of the most important theological contributions to come out of the twentieth century. His contributions in metaphysics, apart from scattered content in the commentaries, are found in Living Time and the Integration of the Life. An important biography of Nicoll is Beryl Pogson’s Maurice Nicoll: A Portrait. This biography is nicely done. A couple additional historical references are James Webb, The Harmonious Circle where I took the quote of Rowland Kenny, and C.S. Nott, Journey Through This World.

Wednesday, June 18, 2008

THE EPISTEMOLOGY OF REVEALED TRUTH

Let me begin with a brief statement about the meaning of epistemology. The term refers to the philosophy of knowing: how do we know, different kinds of knowing, and such issues as the “fit” between the truth content of a knowledge-event and the reality it is supposed to represent. To help you catch onto the point, I’ll use the “fit” statement I just made as an illustration. That “issue” as I presented it actually makes an epistemological assumption. It assumes a dualism between truth and reality, and a “representational” relation between them as in simple mapping. But this is already a presupposed epistemology, and one that has some merit but also has shortcomings in some applications. It is not always appropriate. Does direct perception, like the color of grass, follow this “representational epistemology”? Were you and I to get into a discussion of this question, we would be discussing epistemology.

We do not need a great deal of depth in epistemology for the issue at hand. Notice very simply that there are a variety of ways that we can come to know something. We can read it in a book. We can see it with our eyes; hear it with our ears, etc. We can show elements of instinct, we can measure, we can use instruments, we can watch TV, and we can notice what our emotions are telling us. Ultimately, the vast “stew” of the accumulated content of this knowing becomes unwieldy. We develop philosophies and ideologies to help us make sense of the world and organize our thoughts. And different people at different places and times and different cultural contexts have different philosophies and ideologies, sometimes contradictory one with another. This in itself becomes an issue of epistemology – how do we know how to sort out all this mess of diverse ways of interpreting the world?

Among the various answers that have been presented to this question, one of the common ones largely in vogue in my own time and culture is social relativism. This seems to be especially popular in ethical philosophy. Social relativism honestly notes that people do not agree and that they also don’t agree on criteria to assess their disagreements, and different positions are taken seriously by different people in different places, times and cultures. Therefore, they argue, it is all relative – there are no objective criteria, and no one can say their version of the truth is any better than someone else’s. Taken to the extreme, I sincerely hope that even the social relativists know this would end up absurd: the answer to two plus two is not relative or culturally dependent. The relativists would counter that I miss the point, as they are not talking about such straightforward facts, but opinion issues and perspectives. And the domain of the content of what is included in that is very broad. All of religious doctrine, for example, belongs squarely in this domain. Therefore, they would say, one person’s opinion is as good as another’s essentially. This is popular even among supposedly intelligent people.

I do not see this as intelligent because it leaves no room whatsoever for greater or lesser authority. Sure, people recognize differences of authority in certain categories. No one would let a barber do brain surgery on their child. People seem to understand that in matters of medicine, science, technology and many other fields, there are experts who can be trusted, and these are the people who should be taken seriously. But in matters of the soul, or even very broadly in religion, people will listen to anything. And they will resent even the notion that one should demand a certain credentialed authority. One merely needs to stand behind a pulpit and shout “Jesus” a few times. And yet, it is here as much as anywhere else that competence is critical. It is also exceedingly rare.

But I am not just concerned with people who consider themselves true believers. I wish to include a broad, loosely defined group that includes almost all secularists, agnostics, and casual social “Pharisee” church-goers. There is a certain form of relative religious epistemology that can be seen among all of these. Not many, perhaps, take social relativism to the extreme, but most will give a cold reception to any claims that a person knows better on religious subjects than they themselves or, for that matter, than anyone else. They may admit to more knowledge or academic learning, but not more reliability. It is taken as arrogance. One is supposed to admit that one cannot understand these things. You cannot say that you understand certain things. God’s answer to Job is the ultimate epistemology of religion. It is labeled as humility, but more realistically, it is usually a security blanket for a lazy and cowardly mind.

What I want to make perfectly clear is that social relativism and spirituality are flagrantly contradictory in their epistemologies. Spirituality denotes the idea of the sacred. In terms of human understanding, it specifically denotes a sacred truth. This is usually to be found in certain writings that are considered to be sacred texts. Thus we have the Bible for Christians, the Koran for Muslims, and so on. Now the fundamental premise behind all sacred texts is the idea of revealed truth. This is what makes the texts sacred – what separates them from ordinary writings. What is revealed truth? It is truth that purports to derive from God or some sort of transcendental level beyond that of ordinary mortal consciousness. It is claimed in principle that this gives the truth a level of authority beyond what ordinary mortals can claim in ordinary states. No one who believes in God would say that God’s opinion is merely on a par with everyone else’s. So social relativism does not pertain to God. By extension, it does not pertain to revealed truth. Revealed truth by very definition says that its knowing is at a greater level of authority than ordinary people in ordinary states. Therefore, the epistemology of revealed truth is incompatible with social relativism.

At this point, most people will simply agree and wonder why I am making an issue of this. It is in fact a very important issue, because we have to consider how revealed truth gets to be revealed. We find that the actual ink to the paper comes from human hands. Sacred texts are written in human languages and show human contexts in the times and places of their origin. Structuralists who analyze the texts accordingly might lay bare much of this context, but will face serious challenges trying to unravel the presumed transcendental content. Their toolbox will not have all of the right tools. Sacred texts incorporate built-in metalanguages, as the Russian philosopher P.D. Ouspensky examined in the gospels decades before Barthes. They achieve universalism in time and place (every culture, every age) by means of the tools that can do that: myth, symbol and parable – an insight that, even if not fully articulated, was understood and employed by Jesus, Socrates and Buddha (and their text authors) millennia ago.

Many simplistic religious people tout the Bible as the “Word of God” in such a manner as to suggest that Matthew, Mark, Luke, John, the apostle Paul, Moses and the prophets downloaded God’s word on their PC after God handed it to them on a flash drive. Obviously this issue is complex, and a full analysis is beyond the scope of my intentions here. But I wish to reiterate wording I have already employed and state categorically that ordinary people in ordinary states do not write scripture. This is true if you accept the idea of revealed truth. Of course, if you do not accept that idea, you are renouncing the texts as sacred. In that case, you can be a relativist with these texts and tout your own opinion as just as good as those of Jesus Christ. On the other hand, if you find that suggestion outrageous, you are denouncing relativism in regard to these texts. You can’t have your cake and eat it too – it is either one or the other. And to accept the texts as revealed truth in spite of human authorship requires acceptance of my statement that ordinary people in ordinary states do not write scripture.

We are confronted directly with the mechanism of revelation – how is revealed truth revealed? Simply put, people cross an epistemological threshold by virtue of transcendental inner states collectively appropriate for the domain of mysticism (for a technically accurate definition of mysticism see my June, 2008 blog post “Proper definitions of “mystic” and “mysticism”). So a person undergoes a mystical state (or a master like Jesus or Buddha attains the state permanently) and is privy while in that state to insight unavailable in more ordinary states. This gives the insight of the person a level of authority that cannot be challenged by people in ordinary states without committing the MTE fallacy (see my June, 2008 blog post “The fallacy of Misconstrued Transcendental Empiricism”). Notice that social relativists would simply denounce the validity of the fallacy (which I applied to transcendental states collectively). But many of these people claim to believe in revealed truth. They may get around the contradiction by saying they accept the concept of revealed truth only for certain texts, which came about as a miracle from God. But they continue to “play ostrich” with the mechanism. They have no epistemology. They are back to the flash drive. They are not facing human authorship and its implications.

Now we come to something very interesting. Either we open the door to revealed truth or we do not. If we open that door, we must accept that the door is open and all that is implied by it. We cannot say that the door is open on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays but not on Tuesdays and Thursdays. We cannot say the door is open in Europe and not America. We cannot say that the door was open for Moses but not for Socrates. We cannot say the door was open two thousand years ago but not today. There exists a vast literature of consistent mystical writings that give testimony in virtually all cultures and periods of history to revealed truth. This literature, stripped of cultural embellishments, proclaims in some form or fashion various more-or-less consistent ideas that belong to the body of revealed truth. These ideas are fundamentally consistent in general with the concept of spirituality and its content. Spirituality pertains to the notion of hierarchy in inner development, and the possibility of an inner evolution. In broad strokes, this is what all spirituality proclaims. Revealed truth is consistently concerned with proclaiming that possibility – the “good news” of the gospels – and casting some light upon it. Authentic spiritual traditions ostensibly harbor some portion of an inner technology for achieving this evolution, although the actual practice has always been confined to one-on-one oral teaching and is essentially absent from the literature.

Here we find ourselves confronting the MTE fallacy leering in our face. Notice a very curious thing that has just happened here: we can no longer confine our discussion of relative versus revealed epistemology to the issue of sacred texts. Again, either the door is open or it isn’t. If the door is open to revealed truth it is open universally. There will always be mystics and pseudo-mystics. For the real thing, we cannot rule out the possibility of revealed truth from them unless we rule out the entire concept completely in all applications. Mystics can actually know things that are only opinion issues for others. If you do not accept that, don’t turn around and tell me the Bible is the “Word of God”, because you are contradicting yourself. The mechanism is essentially the same. Either both are possible or neither is possible.

Tuesday, June 17, 2008

PROPER DEFINITIONS OF "MYSTIC" AND "MYSTICISM"

MYSTIC – A person whose mystical experiences have so influenced the person’s perspective and ideology that these cannot be properly understood without taking the mystical aspect into account.

MYSTICISM – The acceptance and understanding of the fact that consciousness is hierarchical [or “holarchical”] and that the hierarchy involves epistemological thresholds extending beyond the level of commonplace human experience.

NOTE: The definition of “mystic” should be straightforward and non-controversial. I am disposed to say the same about the definition of “mysticism” but readily note that the point will likely not be obvious for many. Indeed, the definition will require some elaboration and unraveling for most readers. That is beyond the scope of this document, but I wish to point out that this definition is both precise and universal. “Precise” means that it offers a scalpel to carefully cut away all content that does not belong, while “universal” means that in so doing nothing is eliminated that should not be eliminated. At the present time I will confine myself to a single example of each to illustrate my meaning more fully. In regards to precise, there are many kinds of remarkable experiences, such as powerful ecstatic emotional states. But this content does not in itself qualify the experience as mystical. If an experience is sufficiently remarkable, it may involve some increase in awareness or consciousness, and thereby qualify it as mystical, but it depends on this component specifically for it to so qualify. In regards to universal, I reject – for example - Evelyn Underhill’s definition involving a vector in the experience toward union with God. This restricts mysticism to theological varieties, which is woefully incomplete. A famous example to the contrary is that of Bertrand Russell, one of the greatest minds of the twentieth century. He speaks openly of himself as a mystic and recounts the story of a single five-minute mystical experience that permanently turned him into a staunch pacifist, whereas he was not one before that experience. And yet Bertrand Russell is also well known as a confessed atheist, and his experience did not change that. I cannot claim to have examined all sources of definitions of these terms, but I have examined large numbers over several decades, and found them all inadequate. I am open to discussion of the definitions here, which are from a primary source that I trust – namely, myself. Perhaps in the near future I will post another short document elaborating more fully on some misconceptions about mysticism. Steve Adams, June, 2008

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)